Judicial Power and Independence

Week 4

Who cares about courts?

it is commonly assumed that court rulings must be complied with and followed by affected actors in virtually all constitutional systems

but what are the sources of this judicial power? why and when does anyone listen to courts?

Concept of judicial power

following Staton and Moore (2011), we can usefully identify two pillars of judicial power:

autonomy – or independence in a strict sense – or the extent to which judges’ decisions reflect their true preferences as opposed to someone else’s

effectiveness – or compliance – or the extent to which courts can compel actors to comply with adverse decisions

Concept of judicial power

| High Effectiveness | Low Effectiveness | |

| High Autonomy | Powerful Court | Ignorable Court |

| Low Autonomy | Puppet Court | Joke Court |

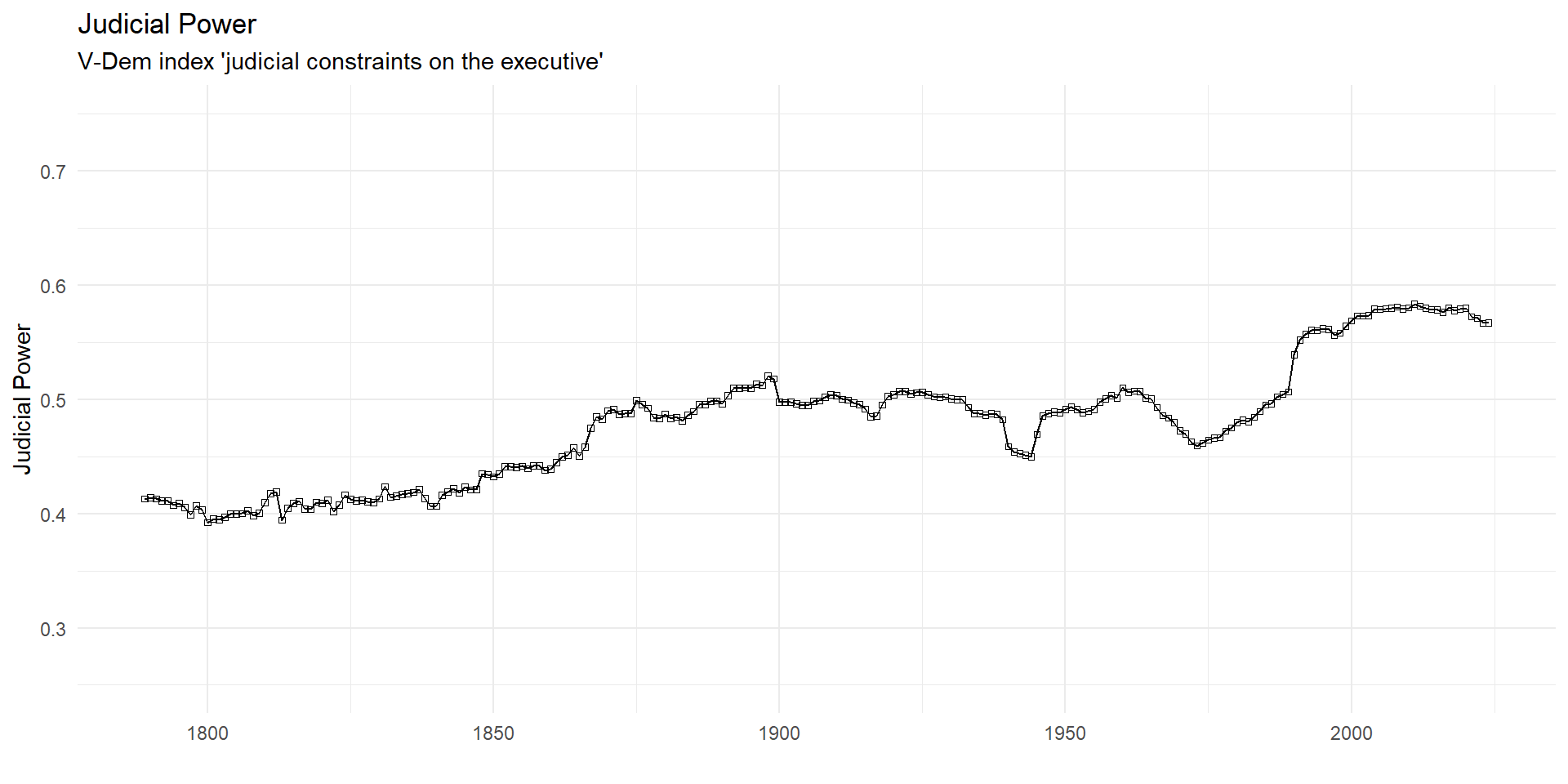

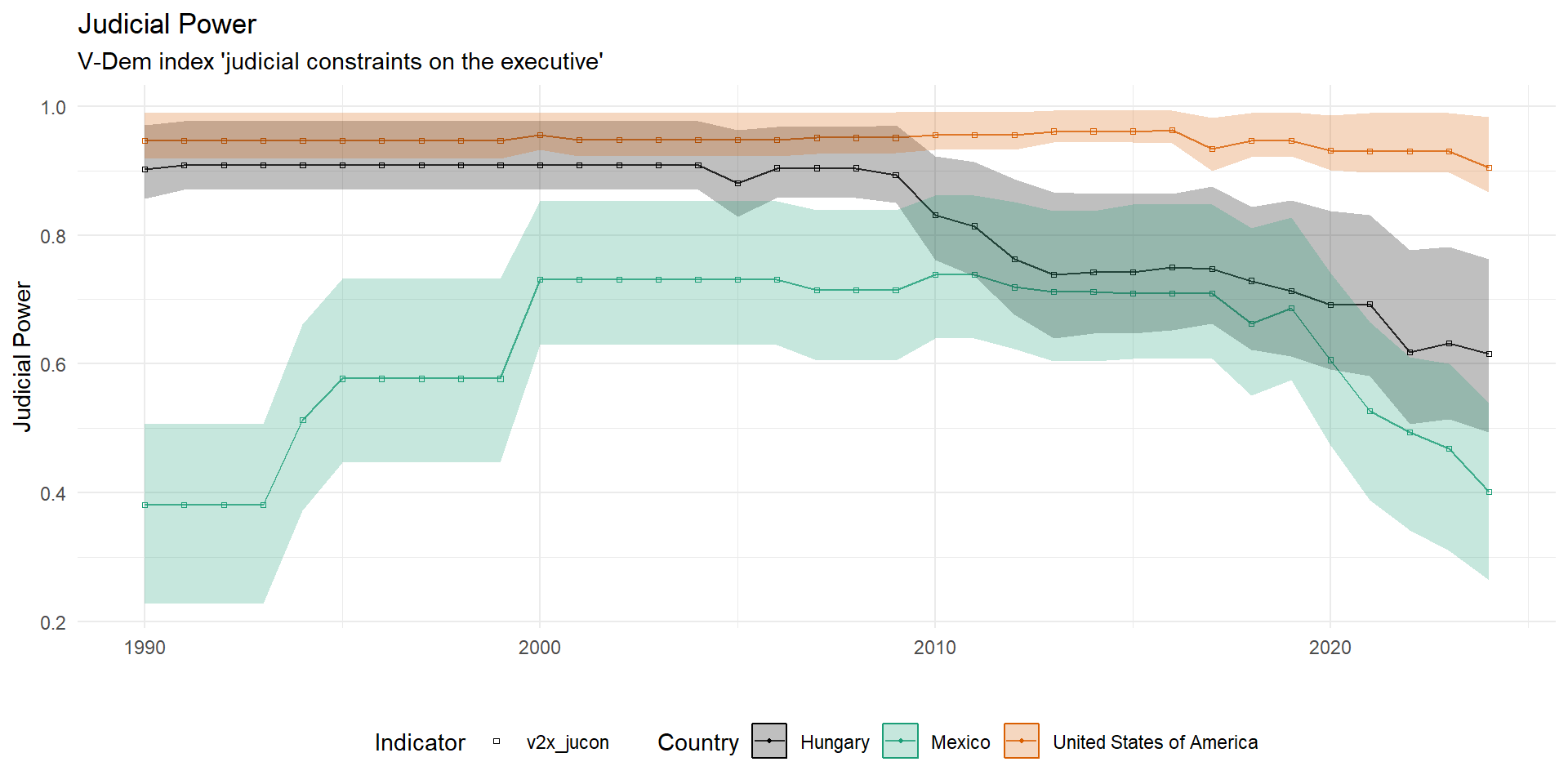

Judicial power in comparative perspective

Judicial power in comparative perspective

Why give courts power?

at the most abstract level the creation and maintenance of a powerful judiciary has been argued to be about credible commitments

by empowering actors (i.e. courts) outside their direct and immediate control, governments signal willingness to be bound by constitutional rules (e.g. respecting property rights) (North and Weingast 1989)

- in the international context, governments signal commitment to jointly negotiated rules (e.g. treaties)

Why empower courts in autocracies?

authoritarian regimes want to keep low-level corruption in check

courts can share the blame for unpopular policies (Ginsburg and Moustafa 2008)

independent enforcement of property rights as a credible commitment to investors

courts are useful for controlling opposition movements

courts can provide regime-friendly interpretations of the law, including the constitution

Insurance theory of court power

empowering courts comes at a cost to executives and legislators

courts are more stable than governments – empowering courts can insure incumbents against loss of power (Finkel 2005)

powerful courts can make it harder to change policy direction

they can also help protect former leaders and their assets

1994 judicial reform in Mexico

after winning elections in 1994 president Ernesto Zedillo decided to make the Mexican judiciary more independent and powerful – why?

Finkel (2005) explains this counterintuitive move as a form of insurance policy

the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party was losing support and anticipated loss of power

the reform gave the Mexican Supreme Court more power to circumscribe (federal and state) government policy

1994 judicial reform in Mexico

Ernesto Zedillo during his presidency

What makes judges autonomous?

judicial independence is the single most important attribute associated with modern judiciaries

yet there is disagreement on the precise content of this concept

independence to do what? independence from what or whom?

Judicial independence

the degree to which judges actually decide cases in accordance with their own determinations of the evidence, the law and justice, free from the coercion, blandishments, interference, or threats from governmental authorities or private citizens. (Rosenn 1987, 8)

What is(n’t) judicial independence

can a judge be independent when the judiciary as a whole isn’t?

does “dependence” on another judge’s or court’s decision undermine judicial independence?

What is(n’t) judicial independence

what about anticipatory judicial behaviour?

- a court may self-censor if it knows the government is likely to override its decision

free from “governmental authorities or private citizens”

rulings based on “own determinations of … the law” vs “the law”

De jure vs de facto independence

many scholars distinguish between “paper” or institutional guarantees of independence and what happens in practice (Melton and Ginsburg 2014; Hayo and Voigt 2007)

the most common de jure guarantees are:

- commitment to judicial independence, life tenure, depoliticized selection procedure, constrained removal procedure, salary non-regression

De jure vs de facto independence

there is mixed evidence on the importance of de jure guarantees of independence on de facto levels

Stiansen (2022) shows that removing re-appointment opportunities made ECtHR judges more likely to rule against the country which nominated them

De jure vs de facto independence

there is doubt whether judicial autonomy can be measured in isolation due to anticipation effects

- judges’ decisions are affected by the likelihood of compliance (Linzer and Staton 2015)

Harvey (2022) suggests to focus on contextualizing de facto independence

- e.g. ruling-party incentives to intervene can vary based on circumstances

Judicial independence in Francoist Spain

Toharia (1975) documents that in the authoritarian Spain of the 1970s, judges held diverse opinions different from the regime

ordinary judges were by and large insulated from threat of removal or punishment by the government

however, the regime interfered with independence in politically sensitive cases by creating and staffing a host of special tribunals

Judicial independence in Francoist Spain

General Franco ruled Spain until 1975

Legal dualism

Hendley (2022) argues that the creation of special tribunals for political issues is the exception in authoritarian regimes

instead, the “normative” and “prerogative” states coexist side-by-side, often relying on informal institutions

e.g. the same judge handling ordinary cases can be twisting the law to enable the persecution of dissidents

Public support as a source of judicial power

one reason why courts’ autonomy and effectiveness can be high is public support (Carrubba and Zorn 2010)

in general, people hold courts in high regard (Vanberg 2015)

- this is helped by the fact that courts are often responsive to public preferences (Mishler and Sheehan 1993)

attacking courts and non-compliance is usually politically costly

How can courts increase their power?

new courts consolidate power by not antagonizing the government for an initial period

expand jurisdiction through broad interpretation of access rules and legal domains

a common strategy is to first create the power-expanding principle without applying it in the initial case to mitigate costs of compliance

References

POLS0113: Judicial Politics