Courts, Executives and Legislatures

Week 6

Strategic interactions

How do courts, executives and legislatures interact in the enactment and enforcement of policy?

How does strategic anticipation of mutual preferences affect how they behave?

Judicial constraints on the executive

- in the classic narrative, independent courts constrain the executive’s discretion, including to engage in arbitrary coercive acts, which benefits economic development (North and Weingast 1989)

- across a sample of 104 countries, de facto (but not de jure) judicial independence is associated with higher growth rates (Voigt, Gutmann, and Feld 2015)

- externally funded judicial reforms in African countries improved perception of the rule of law among relatively powerless groups (Chemin 2021)

- removing presidential discretion in judicial appointments in Pakistan improved decision quality and constrained government discretion (Mehmood 2022)

Separation of powers

even in systems where judicial independence is strong, there are many formal points of contact between the judiciary, the legislature and the executive

appointment of judges

competence disputes

judicial review of administrative acts

judicial review of statutory law

Judicial review

constitutional (and sometimes ordinary) courts have in many jurisdictions the power of judicial review

the legislating body knows its acts can be reviewed

courts depend on the executive branch for enforcement

- public support for courts makes enforcement more likely

Anticipating judicial review

in general, legislators want to avoid having their laws struck down by judges

what is the chance the act will be reviewed?

- shaped by rules on jurisdiction and judicial review

what is the chance the act will be overturned?

- shaped by distance between legislator and court

Anticipating judicial review

the legislature only needs to fear the courts when judicial review is likely to happen

in some countries this is virtually guaranteed (e.g. US), while elsewhere there will be more uncertainty

in the EU, if all political actors agree, there is very low chance of review

the possibility of judicial review can be endogenous to policy making (Pavone and Stiansen 2022)

Anticipating judicial review

the legislature only needs to fear the courts when they prefer to overturn an act

the legislature will look for information on:

the court’s previous case law

judges’ ideological positions

public support

Anticipating judicial review

in reality, no actor has complete and perfect information about the judicial review game

there is uncertainty about how the courts will react

actors sometimes behave irrationally

the legislator might water down an act or otherwise preempt negative judicial action

Anticipating judicial review

in some cases, the legislator will not shy away from judicial conflict (Schroeder 2022)

when they have strong public support (Vanberg 2001; Krehbiel 2016)

when they signal intention to not comply

Anticipating reactions

courts have also reasons to fear confrontation

non-compliance undermines their power and legitimacy

may trigger court curbing by the other branches

just like legislatures do not want to be censored by courts, courts do not want to be overridden by legislatures

(Non-)Compliance

due to courts’ enforcement-dependency, non-compliance is an attractive strategy for other actors (especially other branches of power)

- but non-compliance can itself generate more litigation

in most cases it is less costly for the government/legislator to evade compliance implicitly

- e.g. creating a parliamentary working group but never delivering (Vanberg 2001)

Threat of override

courts may also take into account whether their decision is likely to be overridden by the legislature (Meernik and Ignagni 1997; Larsson 2021)

- though the empirical evidence of override anticipation by courts is mixed (Segal 1997; Segal, Westerland, and Lindquist 2010)

courts are looking for judgments which are as close as possible to their ideal point but not so far as to get overridden

Threat of override

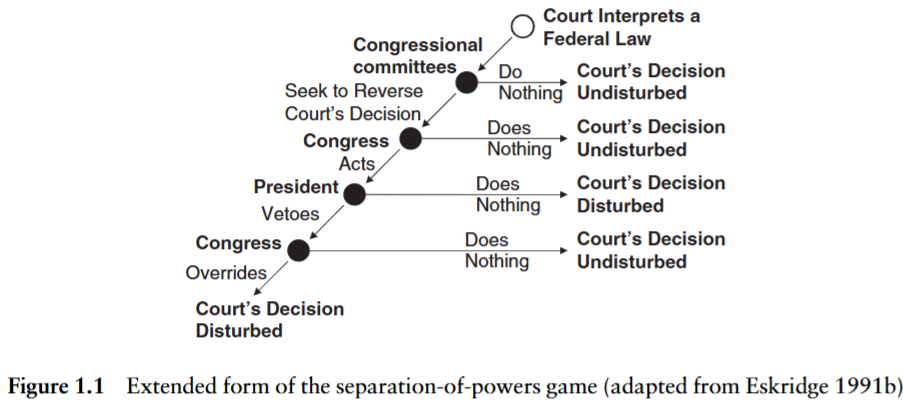

US Override Game from Dyevre (2010)

Threat of override

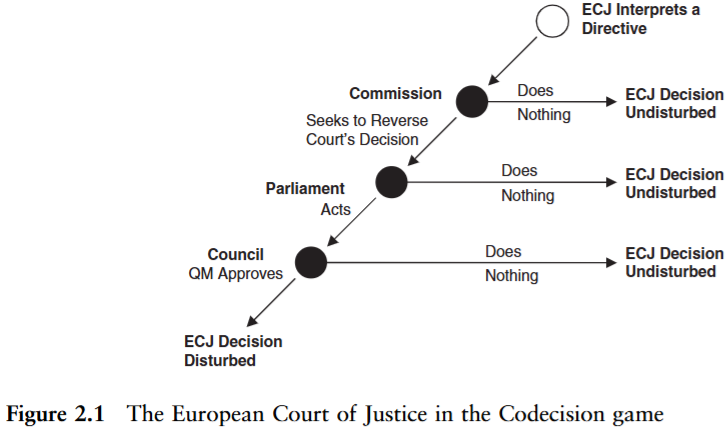

EU Override Game from Dyevre (2010)

Court curbing

the legislator signaling intent to engage in court curbing is likely to lead to judicial self-restraint

a number of possible measures:

budget and staffing cuts

induced judicial exits (e.g. lowering retirement age)

court expansion and packing

limiting jurisdiction and powers

The constrained court

fear of negative repercussions leads to self-censoring by courts

courts are on safer ground when they support popular policies

- leads to the notion of “judicial majoritarianism” (Hall and Ura 2015)

The friendly court

consistent with the idea of the majoritarian court is evidence of courts ruling against policies of previous governments (Segal, Westerland, and Lindquist 2010; Gillman 2002)

a “friendly” judicial intervention can be particularly valuable when it concerns constitutional interpretation that would be otherwise difficult to legislate away (e.g. Roe and Dobbs)

also helps explain why governments might sometimes appear to support “activist” judiciaries (Whittington 2005)

Informal interactions

many interactions between courts and representatives of other branches can occur outside formal contexts

as members of the elite with access to power and resources, both judges and politicians can face incentives to confer special treatment

- eg judges may shield corrupt politicians from prosecution in exchange for bribes or career progress

Informal interactions

transferring jurisdiction outside the local county increased the chance of the local government losing a case by ~4 pp (10%) (Cao, Liu, and Zhou 2023)

(narrowly) winning a seat in Indian state legislature decreases the chance of criminal conviction by ~20 pp, but only for ruling party co-partisans (Poblete-Cazenave 2025)

(narrowly) winning mayoral elections in Brazil reduces chance of conviction by local judges by ~11 pp (65%) (Lambais and Sigstad 2023)

- despite there being no formal power of mayors over judges

de jure separation is not sufficient to capture intended benefits of judicial independence

References

POLS0113: Judicial Politics