Judicial Hierarchy and Organization

Week 7

Assessment

deadline: 6 January 2026

what theory do you want to contribute to with your empirical analysis?

- derive a specific hypothesis from theoretical discussion

what data are you going to use to test your hypothesis?

what method are you going to use to analyse your data?

Empirical paper

Introduction: what is the research puzzle/problem and why is it important?

Literature review: what we already know about the problem from previous research and what gap is going to be addressed by your paper

- examples of a gap: all evidence comes from a single jurisdiction; there is conflicting evidence; existing theories do not account for an important variable; etc.

Theory: a reasoned justification of (the logic behind) your principal expectation (hypothesis) prior to conducting the empirical analysis; must be informed by existing literature

what puzzle does your theory attempt to explain?

example of a hypothesis: “The likelihood of [Supreme Court] review should initially decrease and then increase in ideological distance [from the lower court].”

what is your explanatory (independent) variable? What is your outcome (dependent) variable?

Empirical paper

Data: information used to produce evidence and test your hypothesis

which cases will offer leverage on your research problem?

how do you operationalize your theory (variables) in data? What is the unit of analysis?

what measurement choices were made in the construction of the dataset?

you can use an existing dataset or collect your own data

even in qualitative research keep meticulous track of your sources (transparency appendix)

Methods/research design: the empirical strategy applied to your data in order to test your hypothesis

how do you analyse your data?

what valid inferences can be made based on your method? e.g. average treatment effects vs mechanistic evidence

what are the assumptions and limitations of the method?

Empirical paper

Findings and discussion: the results produced by your empirical strategy and data

what are the results of your analysis?

what are the implications for your hypothesis? is there evidence in support or against it?

what are the implications for the broader theory and literature?

what have we learned that we did not know before?

Conclusion: summarize findings, highlight main contribution and limitations, and offer thoughts on policy and future research avenues

Organizing the judiciary

how are judiciaries organized?

what are the implications of organizational principles for judicial decision-making?

Judicial hierarchy

virtually all judiciaries around the world are organized hierarchically

three “layers” are typical

supreme and constitutional (peak) courts at the top

courts of appeal in the middle

ordinary (lower) courts at the bottom

Judicial hierarchy

peak courts = courts of final instance

no more appeals possible

of special significance in some jurisdictions (e.g. ECtHR)

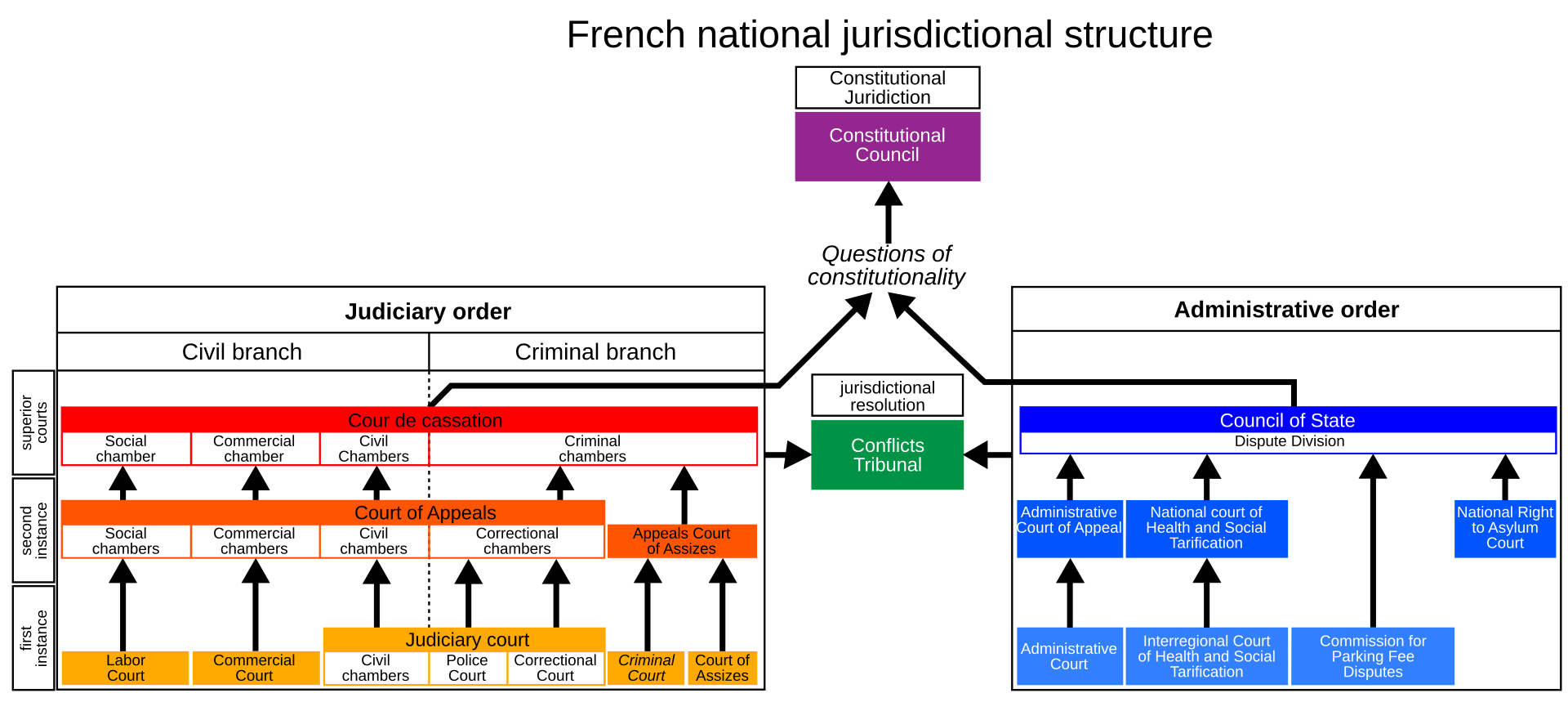

in many systems there are multiple hierarchies

- e.g. military courts or administrative law (France)

Judicial hierarchy

Judicial hierarchy

in some circumstances, judicial hierarchies are not universally accepted

in the EU, the CJEU proclaims the doctrine of supremacy of EU law over national law and its own role as the ultimate arbiter of EU law questions

from the CJEU’s perspective, all national courts must follow its lead

not all national courts accept that the CJEU sits atop the EU law hierarchy

Judicial hierarchy

The Court of Justice of the European Union exceeds its judicial mandate, as determined by the functions conferred upon it in Article 19(1) second sentence of the Treaty on European Union, where an interpretation of the Treaties is not comprehensible and must thus be considered arbitrary from an objective perspective. If the Court of Justice of the European Union crosses that limit, its decisions are no longer covered by Article 19(1) second sentence of the Treaty on European Union in conjunction with the domestic Act of Approval; at least in relation to Germany, these decisions lack the minimum of democratic legitimation necessary under Article 23(1) second sentence in conjunction with Article 20(1) and (2) and Article 79(3) of the Basic Law.

German Constitutional Court, Judgment of the Second Senate of 5 May 2020, press release

Judicial hierarchy

judges at different levels of the pyramid face different pressures and incentives

at the bottom, the range of goals is the widest (e.g. routines, workload, promotion, policy)

at the top, judges are mostly concerned with policy considerations and ideological influence is therefore the strongest (Zorn and Bowie 2010)

Judicial motivation

Goto (2026) presents evidence of judicial pandering in Indian courts

judicial leaders hold power over lower courts’ judges promotion prospects

eligible judges become more likely to acquit female defendants and less likely to acquit male defendants in the presence of a female chief justice

Judicial discipline

discipline in the judicial hierarchy is maintained through two mechanisms:

precedents or rules created by higher courts to be followed by lower courts

oversight by higher courts or the threat of reversing lower court decisions

Role of precedent

even jurisdictions which do not formally subscribe to stare decisis usually employ precedents

precedents transmit rules through time and the judicial hierarchy

courts higher in the hierarchy and later in time can amend or expunge lower or previous precedents

Role of lower courts

in the standard account, lower courts implement the doctrines developed by peak courts

they may try to make use of ambiguity to create room for their own preferences (Cameron, Segal, and Songer 2000)

upper courts correct their “errors”

in the ‘reversed’ account, lower courts make their own doctrines (Carrubba and Clark 2012)

they have a first-mover advantage and are closer to case facts

upper courts intervene when lower courts go too far

The cost of review

upper courts do not have direct and immediate access to case facts, only to lower courts’ decisions

they need to spend time and resources to find out more

=> upper courts need to decide which decisions are worth auditing

upper courts care about lower courts’ dispositions and rules

- lower courts choose rules to avoid review (Carrubba and Clark 2012)

The cost of review

the ideal situation for the lower court is when the disposition aligns with the upper court’s preferences

suppose the lower court prefers a liberal rule, while the upper court is more conservative. The facts are so extreme that almost any rule yields a “conservative” disposition (e.g. harsh sentence). The lower can push the rule in a liberal direction because the upper court will be satisfied with the disposition regardless

The threat of reversal

why do lower courts follow precedent? why do they fear reversal?

reputation

belief in legal principles (Cross 2005)

they want to have influence over the law (Carrubba and Clark 2012)

interpersonal contacts between lower and appeal judges dampen the effect of ideological distance (Nelson, Hazelton, and Hinkle 2022)

- when the lower and appeal judges work in the same courthouse, ideological distance becomes irrelevant

The threat of reversal

appeal courts pick up on signals (“fire alarms” / whistleblowing) about whether a decision is worth reviewing

litigants filing appeals

interest groups filing amici curiae briefs

lower court judges dissenting (Beim, Hirsch, and Kastellec 2014)

The effect of reversal

- trial judges in Norway who had their ruling overturned on appeal shift their behaviour in the corresponding direction (Bhuller and Sigstad 2025)

- “Following a decision reversal, trial judges who receive a sentence increase have almost 40 percentage points higher probability of incarcerating in the next case, compared to judges receiving a sentence affirmance”

- judges do not merely “learn” from reversals but overreact to them

The effect of reversal

in the European Union, national courts submit cases to the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU). What happens these cases are rejected by the CJEU?

national courts receiving such a negative result are more likely to submit another case (Dyevre, Lampach, and Glavina 2022)

- the CJEU is more likely to accept requests from national courts that previously experienced rejection

Collegial courts

most important courts are collegial – they involve bargaining between multiple judges

if opinion amendments by judges are costless, the result will align with the median judge’s preferences

- if they are not, the opinion writer can pull the judgment slightly away from the median judge (Hangartner, Lauderdale, and Spirig 2025)

Collegial courts

judges are affected by the ideology, gender and race of the judges they co-decide with (Kastellec 2013)

judges’ mutual familiarity fosters openness and more extensive deliberation (Swalve 2022)

Role of chambers

to increase efficiency, courts can create chambers consisting of sub-groups of judges

their composition can be more or less permanent and stable

but they undermine the court’s consistency in applying rules (Fjelstul 2023)

Case assignment

who decides who decides?

in some courts (e.g. CJEU), the president chooses the opinion writer (judge-rapporteur)

a source of power to steer decisions in a desired direction (Hermansen 2020)

at SCOTUS, the initial majority also gets the pen-holder (Lax and Cameron 2007)

Case assignment

automatic systems of random case assignment as an anti-corruption measure (Marcondes, Peixoto, and Stern 2019)

in some settings assignment of cases is plausibly quasi-random in expectation (Goldsmith-Pinkham, Hull, and Kolesár 2025)

conditional on some covariates, judges are assigned cases as if randomly

more likely to hold when there is a large volume of cases

Role of clerks

judges do not work alone – they are assisted by law clerks

- their influence can be considerable and their selection is not random (Badas, Sanders, and Stauffer 2024)

judges, similar to politicians have different styles

- some are more willing to trust and delegate work than others

References

POLS0113: Judicial Politics