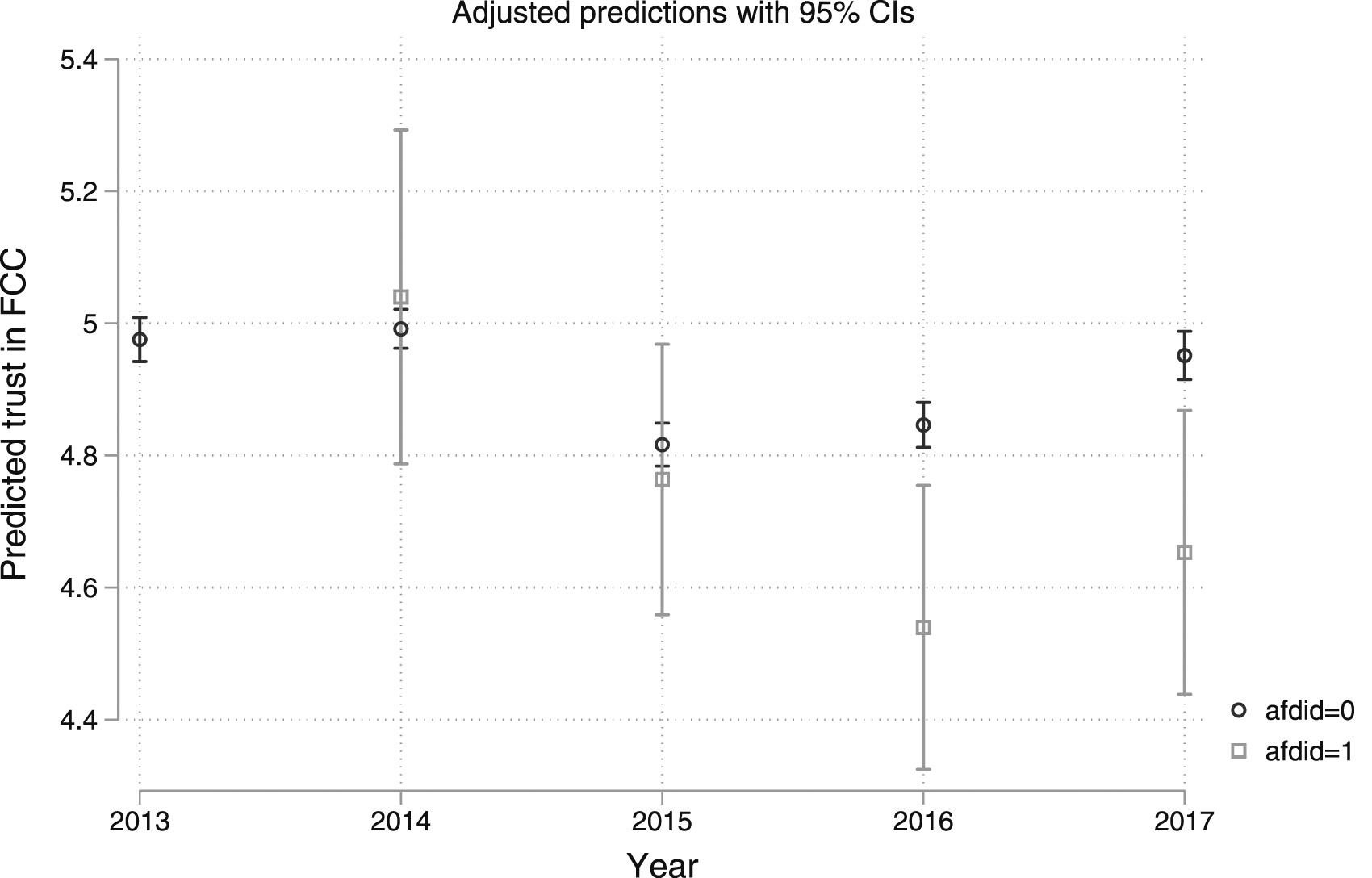

Arzheimer, Kai. 2024.

“Identification with an Anti-System Party Undermines Diffuse Political Support: The Case of Alternative for Germany and Trust in the Federal Constitutional Court.” Party Politics, March, 13540688241237493.

https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688241237493.

Bartels, Brandon L., Jeremy Horowitz, and Eric Kramon. 2023.

“Can Democratic Principles Protect High Courts from Partisan Backlash? Public Reactions to the Kenyan Supreme Court’s Role in the 2017 Election Crisis.” American Journal of Political Science 67 (3): 790–807.

https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12666.

Bartels, Brandon L., and Christopher D. Johnston. 2013.

“On the Ideological Foundations of Supreme Court Legitimacy in the American Public.” American Journal of Political Science 57 (1): 184–99.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2012.00616.x.

Bartels, Brandon L., and Eric Kramon. 2020.

“Does Public Support for Judicial Power Depend on Who Is in Political Power? Testing a Theory of Partisan Alignment in Africa.” American Political Science Review 114 (1): 144–63.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000704.

Bracic, Ana, Mackenzie Israel-Trummel, Tyler Johnson, and Kathleen Tipler. 2023.

““Because He Is Gay”: How Race, Gender, and Sexuality Shape Perceptions of Judicial Fairness.” The Journal of Politics, October.

https://doi.org/10.1086/723996.

Caldeira, Gregory A., and James L. Gibson. 1992.

“The Etiology of Public Support for the Supreme Court.” American Journal of Political Science 36 (3): 635–64.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2111585.

Casillas, Christopher J., Peter K. Enns, and Patrick C. Wohlfarth. 2011.

“How Public Opinion Constrains the U.S. Supreme Court.” American Journal of Political Science 55 (1): 74–88.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00485.x.

Cheruvu, Sivaram, Jay N. Krehbiel, and Samantha Mussell. 2025.

“Partisanship, Pragmatism, or Idealism? Evaluating Public Support for Backlashes Against International Courts in Backsliding Democracies.” Journal of European Public Policy, February.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13501763.2024.2351921.

Cohen, Harlan, and Ryan Powers. 2024.

“Judicialization and Public Support for Compliance with International Commitments.” International Studies Quarterly 68 (3): sqae078.

https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqae078.

Gandur, Martín, Taylor Kinsley Chewning, and Amanda Driscoll. 2025.

“Awareness of Executive Interference and the Demand for Judicial Independence: Evidence from Four Constitutional Courts.” Journal of Law and Courts, January, 1–26.

https://doi.org/10.1017/jlc.2024.20.

Gibson, James L. 2024.

“Losing Legitimacy: The Challenges of the Dobbs Ruling to Conventional Legitimacy Theory.” American Journal of Political Science 68 (3): 1041–56.

https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12834.

Gibson, James L., Milton Lodge, and Benjamin Woodson. 2014.

“Losing, but Accepting: Legitimacy, Positivity Theory, and the Symbols of Judicial Authority.” Law & Society Review 48 (4): 837–66.

https://doi.org/10.1111/lasr.12104.

Gibson, James L., and Michael J. Nelson. 2017.

“Reconsidering Positivity Theory: What Roles Do Politicization, Ideological Disagreement, and Legal Realism Play in Shaping U.S. Supreme Court Legitimacy?” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 14 (3): 592–617.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jels.12157.

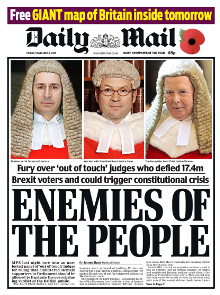

Gonzalez-Ocantos, Ezequiel, and Elias Dinas. 2019.

“Compensation and Compliance: Sources of Public Acceptance of the U.K. Supreme Court’s Brexit Decision.” Law & Society Review 53 (3): 889–919.

https://doi.org/10.1111/lasr.12421.

Helfer, Laurence R, and Erik Voeten. 2020.

“Walking Back Human Rights in Europe?” European Journal of International Law 31 (3): 797–827.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chaa071.

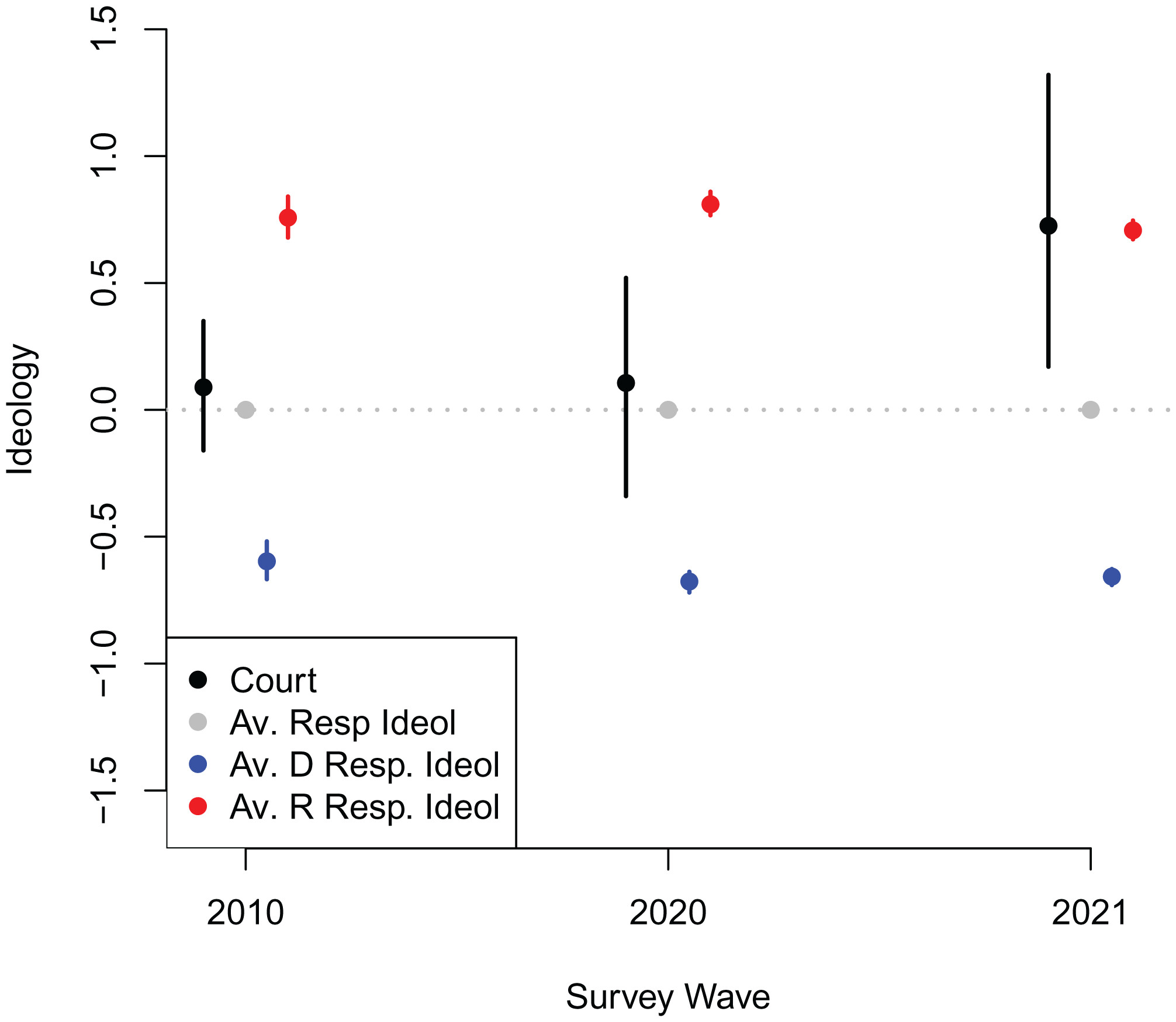

Jessee, Stephen, Neil Malhotra, and Maya Sen. 2022.

“A Decade-Long Longitudinal Survey Shows That the Supreme Court Is Now Much More Conservative Than the Public.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119 (24): e2120284119.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2120284119.

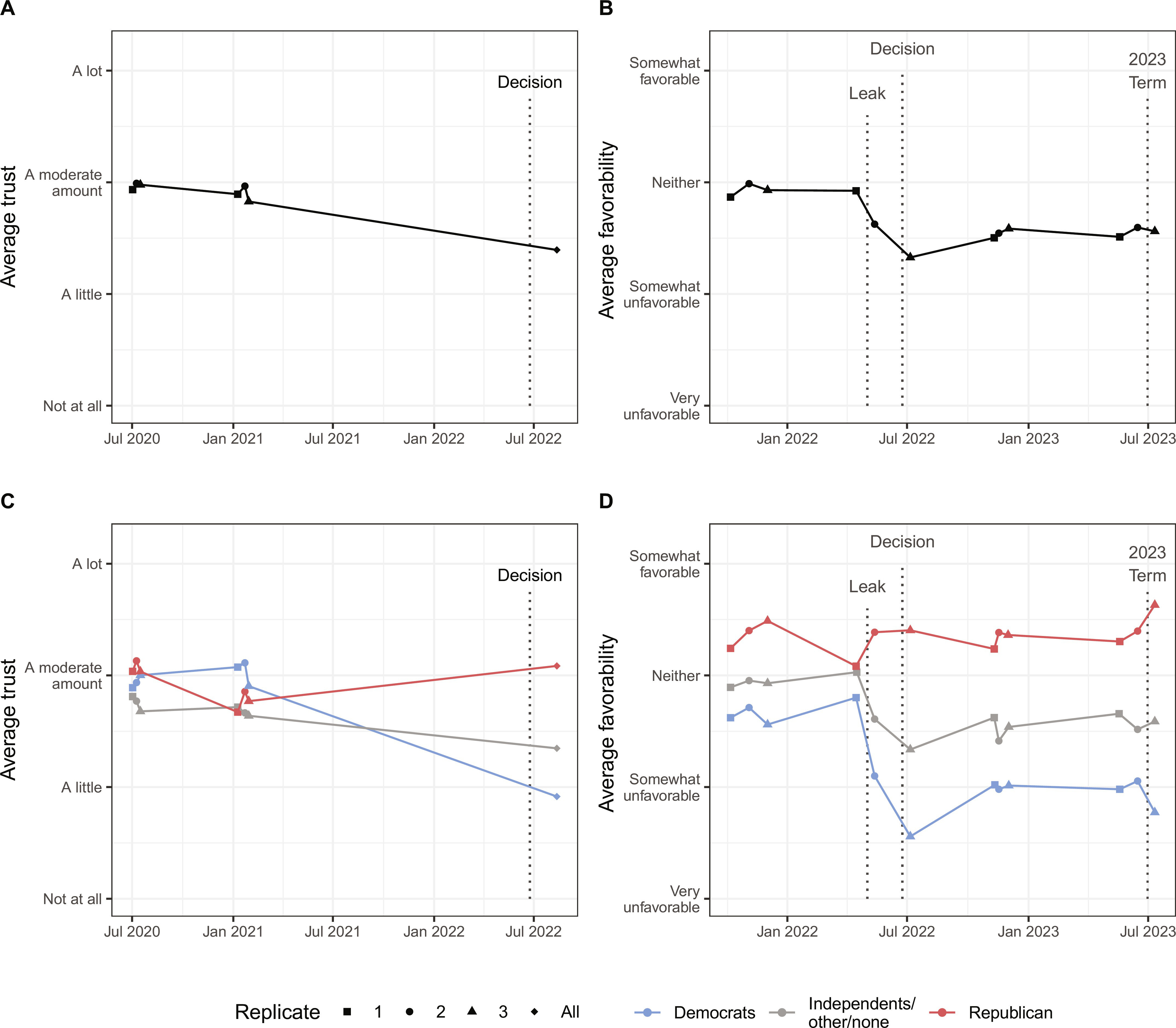

Levendusky, Matthew, Shawn PattersonJr, Michele Margolis, Josh Pasek, Kenneth Winneg, and Kathleen H. Jamieson. 2024.

“Has the Supreme Court Become Just Another Political Branch? Public Perceptions of Court Approval and Legitimacy in a Post-Dobbs World.” Science Advances, March.

https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adk9590.

Linos, Katerina, and Kimberly Twist. 2016.

“The Supreme Court, the Media, and Public Opinion: Comparing Experimental and Observational Methods.” The Journal of Legal Studies 45 (2): 223–54.

https://doi.org/10.1086/687365.

Madsen, Mikael Rask, Juan A. Mayoral, Anton Strezhnev, and Erik Voeten. 2022.

“Sovereignty, Substance, and Public Support for European Courts’ Human Rights Rulings.” American Political Science Review 116 (2): 419–38.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421001143.

Magalhães, Pedro C., Jon K. Skiple, Miguel M. Pereira, Sveinung Arnesen, and Henrik L. Bentsen. 2023.

“Beyond the Myth of Legality? Framing Effects and Public Reactions to High Court Decisions in Europe.” Comparative Political Studies 56 (10): 1537–66.

https://doi.org/10.1177/00104140231152769.

Micheli, David De, and Whitney K. Taylor. 2024.

“Public Trust in Latin America’s Courts: Do Institutions Matter?” Government and Opposition 59 (1): 146–67.

https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2022.6.

Stappert, Nora, and Soetkin Verhaegen. 2025.

“Between Contestation and Support: Explaining Elites’ Confidence in the International Criminal Court.” Law & Social Inquiry 50 (1): 249–83.

https://doi.org/10.1017/lsi.2024.18.

Sternberg, Sebastian, Sylvain Brouard, and Christoph Hönnige. 2022.

“The Legitimacy-Conferring Capacity of Constitutional Courts: Evidence from a Comparative Survey Experiment.” European Journal of Political Research 61 (4): 973–96.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12480.

Stiansen, Øyvind, and Erik Voeten. 2020. “Backlash and Judicial Restraint: Evidence from the European Court of Human Rights.” International Studies Quarterly 64 (4): 770–84.

Tyler, Tom R. 2006.

“Psychological Perspectives on Legitimacy and Legitimation.” Annual Review of Psychology 57 (1): 375–400.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190038.

Voeten, Erik. 2020.

“Populism and Backlashes Against International Courts.” Perspectives on Politics 18 (2): 407–22.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592719000975.

———. 2022.

“Is the Public Backlash Against Globalization a Backlash Against Legalization and Judicialization?” International Studies Review 24 (2): viac015.

https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viac015.

Zvobgo, Kelebogile, and Stephen Chaudoin. 2025.

“Complementarity and Public Views on Overlapping International and Domestic Courts.” The Journal of Politics 87 (3): 1028–44.

https://doi.org/10.1086/732982.